-

1. Getting Started

- 1.1 About Version Control

- 1.2 A Short History of Git

- 1.3 What is Git?

- 1.4 The Command Line

- 1.5 Installing Git

- 1.6 First-Time Git Setup

- 1.7 Getting Help

- 1.8 Summary

-

2. Git Basics

- 2.1 Getting a Git Repository

- 2.2 Recording Changes to the Repository

- 2.3 Viewing the Commit History

- 2.4 Undoing Things

- 2.5 Working with Remotes

- 2.6 Tagging

- 2.7 Git Aliases

- 2.8 Summary

-

3. Git Branching

- 3.1 Branches in a Nutshell

- 3.2 Basic Branching and Merging

- 3.3 Branch Management

- 3.4 Branching Workflows

- 3.5 Remote Branches

- 3.6 Rebasing

- 3.7 Summary

-

4. Git on the Server

- 4.1 The Protocols

- 4.2 Getting Git on a Server

- 4.3 Generating Your SSH Public Key

- 4.4 Setting Up the Server

- 4.5 Git Daemon

- 4.6 Smart HTTP

- 4.7 GitWeb

- 4.8 GitLab

- 4.9 Third Party Hosted Options

- 4.10 Summary

-

5. Distributed Git

- 5.1 Distributed Workflows

- 5.2 Contributing to a Project

- 5.3 Maintaining a Project

- 5.4 Summary

-

6. GitHub

-

7. Git Tools

- 7.1 Revision Selection

- 7.2 Interactive Staging

- 7.3 Stashing and Cleaning

- 7.4 Signing Your Work

- 7.5 Searching

- 7.6 Rewriting History

- 7.7 Reset Demystified

- 7.8 Advanced Merging

- 7.9 Rerere

- 7.10 Debugging with Git

- 7.11 Submodules

- 7.12 Bundling

- 7.13 Replace

- 7.14 Credential Storage

- 7.15 Summary

-

8. Customizing Git

- 8.1 Git Configuration

- 8.2 Git Attributes

- 8.3 Git Hooks

- 8.4 An Example Git-Enforced Policy

- 8.5 Summary

-

9. Git and Other Systems

- 9.1 Git as a Client

- 9.2 Migrating to Git

- 9.3 Summary

-

10. Git Internals

- 10.1 Plumbing and Porcelain

- 10.2 Git Objects

- 10.3 Git References

- 10.4 Packfiles

- 10.5 The Refspec

- 10.6 Transfer Protocols

- 10.7 Maintenance and Data Recovery

- 10.8 Environment Variables

- 10.9 Summary

-

A1. Appendix A: Git in Other Environments

- A1.1 Graphical Interfaces

- A1.2 Git in Visual Studio

- A1.3 Git in Visual Studio Code

- A1.4 Git in IntelliJ / PyCharm / WebStorm / PhpStorm / RubyMine

- A1.5 Git in Sublime Text

- A1.6 Git in Bash

- A1.7 Git in Zsh

- A1.8 Git in PowerShell

- A1.9 Summary

-

A2. Appendix B: Embedding Git in your Applications

- A2.1 Command-line Git

- A2.2 Libgit2

- A2.3 JGit

- A2.4 go-git

- A2.5 Dulwich

-

A3. Appendix C: Git Commands

- A3.1 Setup and Config

- A3.2 Getting and Creating Projects

- A3.3 Basic Snapshotting

- A3.4 Branching and Merging

- A3.5 Sharing and Updating Projects

- A3.6 Inspection and Comparison

- A3.7 Debugging

- A3.8 Patching

- A3.9 Email

- A3.10 External Systems

- A3.11 Administration

- A3.12 Plumbing Commands

1.1 Getting Started - About Version Control

This chapter will be about getting started with Git. We will begin by explaining some background on version control tools, then move on to how to get Git running on your system and finally how to get it set up to start working with. At the end of this chapter you should understand why Git is around, why you should use it and you should be all set up to do so.

About Version Control

What is “version control”, and why should you care? Version control is a system that records changes to a file or set of files over time so that you can recall specific versions later. For the examples in this book, you will use software source code as the files being version controlled, though in reality you can do this with nearly any type of file on a computer.

If you are a graphic or web designer and want to keep every version of an image or layout (which you would most certainly want to), a Version Control System (VCS) is a very wise thing to use. It allows you to revert selected files back to a previous state, revert the entire project back to a previous state, compare changes over time, see who last modified something that might be causing a problem, who introduced an issue and when, and more. Using a VCS also generally means that if you screw things up or lose files, you can easily recover. In addition, you get all this for very little overhead.

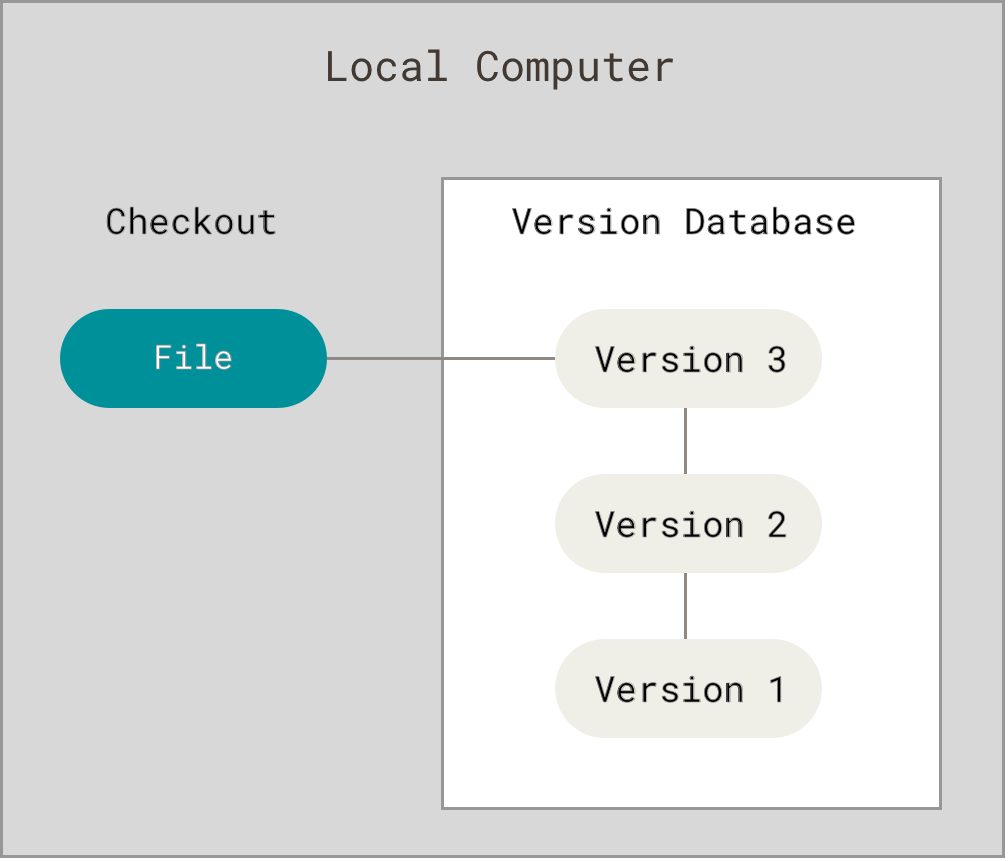

Local Version Control Systems

Many people’s version-control method of choice is to copy files into another directory (perhaps a time-stamped directory, if they’re clever). This approach is very common because it is so simple, but it is also incredibly error prone. It is easy to forget which directory you’re in and accidentally write to the wrong file or copy over files you don’t mean to.

To deal with this issue, programmers long ago developed local VCSs that had a simple database that kept all the changes to files under revision control.

One of the most popular VCS tools was a system called RCS, which is still distributed with many computers today. RCS works by keeping patch sets (that is, the differences between files) in a special format on disk; it can then re-create what any file looked like at any point in time by adding up all the patches.

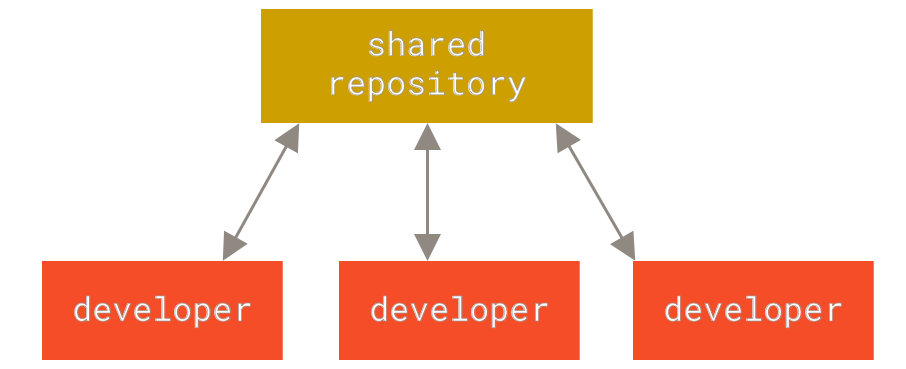

Centralized Version Control Systems

The next major issue that people encounter is that they need to collaborate with developers on other systems. To deal with this problem, Centralized Version Control Systems (CVCSs) were developed. These systems (such as CVS, Subversion, and Perforce) have a single server that contains all the versioned files, and a number of clients that check out files from that central place. For many years, this has been the standard for version control.

This setup offers many advantages, especially over local VCSs. For example, everyone knows to a certain degree what everyone else on the project is doing. Administrators have fine-grained control over who can do what, and it’s far easier to administer a CVCS than it is to deal with local databases on every client.

However, this setup also has some serious downsides. The most obvious is the single point of failure that the centralized server represents. If that server goes down for an hour, then during that hour nobody can collaborate at all or save versioned changes to anything they’re working on. If the hard disk the central database is on becomes corrupted, and proper backups haven’t been kept, you lose absolutely everything — the entire history of the project except whatever single snapshots people happen to have on their local machines. Local VCSs suffer from this same problem — whenever you have the entire history of the project in a single place, you risk losing everything.

Distributed Version Control Systems

This is where Distributed Version Control Systems (DVCSs) step in. In a DVCS (such as Git, Mercurial, Bazaar or Darcs), clients don’t just check out the latest snapshot of the files; rather, they fully mirror the repository, including its full history. Thus, if any server dies, and these systems were collaborating via that server, any of the client repositories can be copied back up to the server to restore it. Every clone is really a full backup of all the data.

Furthermore, many of these systems deal pretty well with having several remote repositories they can work with, so you can collaborate with different groups of people in different ways simultaneously within the same project. This allows you to set up several types of workflows that aren’t possible in centralized systems, such as hierarchical models.